Baby Cognitive Development Through Stage-Based Play

A Program for the First Two Critical Years

The SmartBabies App shows parents what they can do to develop their babies' full intellectual potential!

Babies are born knowledge-seeking, knowledge-making, know-how inventing beings.

The SmartBabies App shows you how to play with babies at every stage of their development.

The activities are geared towards the way your baby develops and learns.

Don’t teach your baby a repertoire of tricks, or empty verbalisms.

Use activities matched to your baby’s abilities, geared to how your baby…

Discovers

Invents

Thinks

What is SmartBabies?

Program Description

SmartBabies is a cognitive development program that is designed to help you engage your child so she can grow to be a problem solver, creative, imaginative, curious, interested in discovering, and yes, inventing. The overall goal is to enrich the inventive nature of your child. With over 110 brief animated videos covering explanations and intellectually enhancing activities, SmartBabies offers a balanced and accessible program for infant and toddler development based on the six recognized stages of early intellectual growth.

Why Start Early

The first 2 years are the most important in your child’s development and set the foundation for everything to follow.

Once born, a baby’s brain grows faster in his first two years than at any other time of his life.

By the age of three, his brain forms approximately 1000 trillion cell connections.

Early experience changes the brain, influencing the brain’s ability to function.

Intellectual growth is nearly complete before a child enters school.

There is no more critical time in human intellectual development.

Before You Begin

CLICK HERE TO VIEW A 2-MINUTE VIDEO

Why Choose the SmartBabies App?

Three Reasons to Choose Us...

1 Jean Piaget

Built from a brilliant mind!

2 Saied H. Jacob

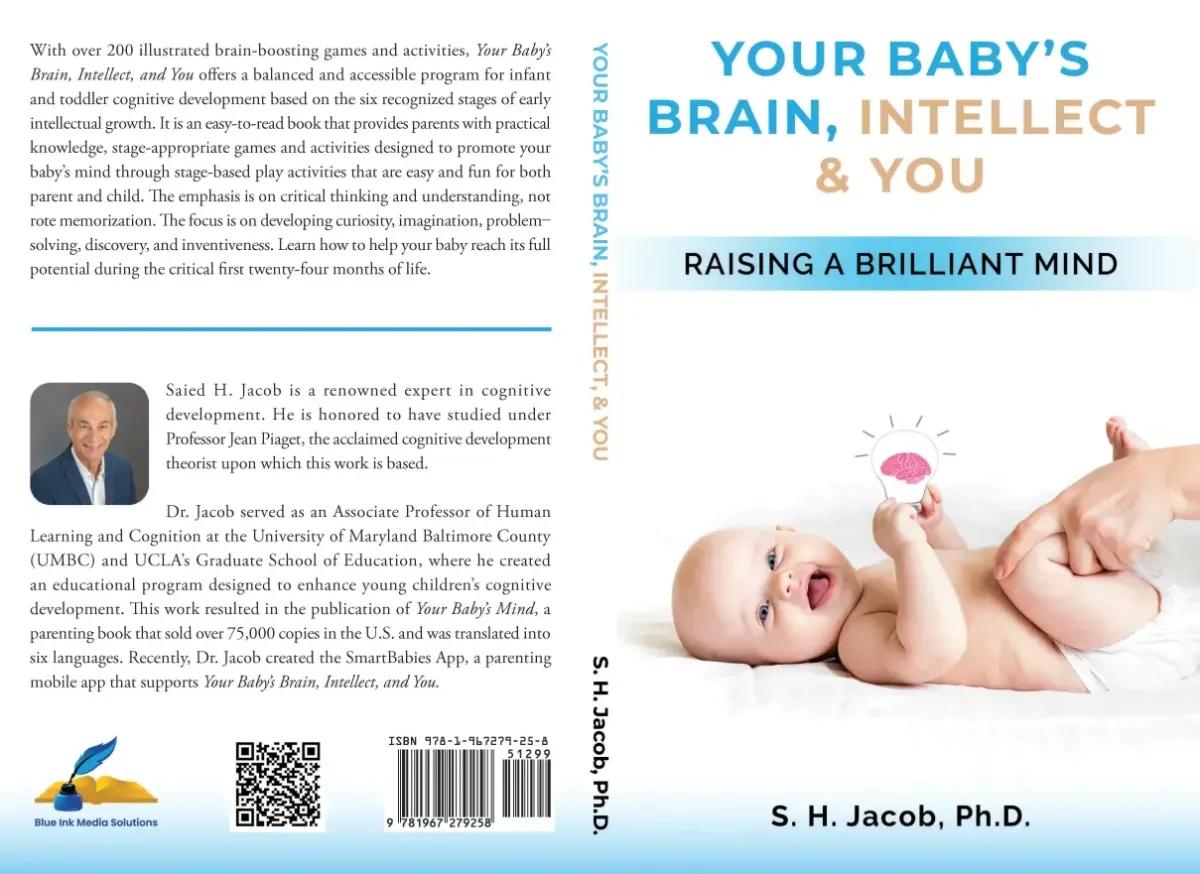

Written by Saied H. Jacob, Ph.D. who studied under Piaget. Dr. Jacob developed an educational system that extends this intellectual giant’s work to its educational limits.

The concepts upon which the SmartBabies App are based are detailed in Dr. Jacob’s numerous books, most notably Foundations for Piagetian Education and Your Baby’s Mind: How to Make the Most of the Critical First Two Years, and most recently, Your Baby Brain, Intellect, and You..

3 Based on scientific evidence.

Based on scientific work in developmental psychology and neuroscience.

About SmartBabies

Do you want your baby to just memorize and parrot things she doesn’t understand?

Or do you want your child to understand?

With our animated, easy to use app, you will be able to empower your baby to:

learn how to learn

learn how to think as a problem solver, explorer, innovator & inventor!

Developmental Stages

Babies and children develop in discrete, well-known stages. With knowledge of these stage, you can enhance and enrich your baby's life by playing games and engaging in activities that excite her because they match the stage in which she is in – they are stage-appropriate. This is a vitally important process. Neglecting cognitive development can lead to boredom and perhaps even an incomplete preparation for later childhood. By the same token, pushing a child ahead of her own development runs the risk of leaving her frustrated, stressed, and convinced that most of her efforts will yield only a sense of failure.

The Six Stages of Cognitive Development

In the First Two Years

Stage 1 – Birth to 1 Month

Newborns are restricted to the use of reflex actions. Because their knowledge system is tied to such ways of knowing as grasping, sucking, eye-movements, etc., things are known only if they trigger these reflex actions. For example, when a nipple touches the area of a baby’s mouth, sucking begins. Such knowledge, or more precisely, such adaptations, are simply survival instincts. Moreover, these reflexes are not integrated with one another. They act independently from one another. Sucking and grasping, for example, are not put together into a coherent single action.

Stage 2 – 1 to 4 Months

Stage 2 babies develop a way of knowing that is superior to the rigid, fragmented way of knowing of Stage 1 babies: they learn to coordinate one reflex action with another, creating new action patterns that are more organized, elaborate, and complete. Stage 2 ushers in the possibility for acquiring new patterns of behavior because of integrating one act with another, then undoing the integration to coordinate acts in an entirely new way. The ability to coordinate and differentiate actions enables the baby to construct new ways of doing things, new ways of organizing and adapting to reality. This expands the realm of learning, enabling the baby to start “playing” and “imitating.”

Stage 3 – 4 to 8 Months

The ability to exercise skills by manipulating the external world of objects is the distinguishing characteristic of the Stage 3 baby (four to eight months). Baby can now reproduce an outcome that she had caused accidentally and found interesting. For example, when she thrashes her legs around in her crib, she notices that the mobile suspended above her moves. She thrashes around again, trying to make the mobile move once more. If she is successful, she will repeat the process again and again. She enjoys repeating the pattern of behavior she has just learned. She is forming a practical understanding of cause and effect, or the means-ends principle. Doing this, she had learned, produces that!

Stage 4 – 8 to 12 Months

After the rapid learning of Stage 3, the Stage IV baby (eight to twelve months) is busy consolidating her past learning and applying it to new situations. This is a time of reconciling the attainments of the past and extending them to new and different situations. In this stage several major attainments are being perfected, beginning with the concept of means-ends relations. The infant now knows an intentional, as opposed to accidental, selection of means to accomplish pre-established goals, and is developing his concept of space and time more fully. On a practical level only, concepts such as “in”, “out”, “behind”, “through”, etc., are understood. This helps the infant attain understanding of the concept of the permanence of objects. In the previous stage, baby could only search for a disappearing object visually; now, he begins to search manually! This important development shows the child’s advancement in understanding that objects can go out of sight without totally vanishing from the world.

Peek-a-boo becomes intensely interesting in this stage; the game gives the baby a chance to confirm this new understanding. Imitating has progressed to the point where the baby can reproduce an action that involves parts of her body she cannot see. Anticipation – associating certain events when they are preceded by others – is also being perfected. When a sequence is disrupted, the element of surprise enters her world.

Stage 5 – 12 to 18 Months

Now a toddler, the Stage 5 child (twelve to eighteen months) can experiment and solve problems, initially through trial and error, but later, quite efficiently. She intentionally and systematically varies an action to discover how changes in her actions effect outcomes. She understands that not only she, but other people and objects can cause things to happen. She has constructed some idea of time, of space, and of how objects fit in and out of things. She knows that if an object has been moved from one hiding place to another, she’ll find it by looking where it was last seen. And she can imitate novel acts – acts that she has not imitated before. Because she is beginning to develop the capacity to represent objects and events mentally through images, words, and abbreviated actions, she is freed from a knowledge system that was restricted to what she could touch, see, hear, smell, and taste. Now she is able to know things by imaging them. When it is completed, what an incredible accomplishment that will be! Stage V is the beginning of the end of sensory-motor intelligence. Over the next year or so, the symbolic system will have evolved to the point where an entirely new age of knowing becomes possible, the age of the wonderful, magical, make-believe world of early childhood.

Stage 6 – 18 thru 24 Months

In this last stage of the Sensory-motoric period (eighteen to twenty-four months), the symbolic system is so well developed that children can solve problems without resorting to the trial-and-error experimentation of the Stage 5 child; they can run through the solution to a problem mentally and then solve it. Stage 6 is a transition period, one that, upon its completion, will hurl the child into the world of thought. Parents delight in witnessing phenomenon of insight. when confronted with a problem, the child shows little or no physical groping before hitting on a solution. As this period ends, a new mode Even though your newborn is completely dependent on you, she is ready to learn. She can SEE, HEAR, FEEL, TASTE, and SMELL. Just as important, she arrives with the ability to ACT. This comes in the form of reflexes, such as sucking, rooting, blinking, and grasping.

The Science Behind Our Program

The SmartBabies App rests on three pillars of knowledge...

1

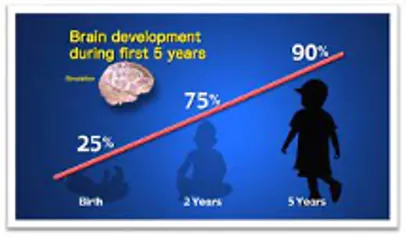

Brain Growth

This incredible growth spurt continues after birth.

A child’s brain undergoes an astounding period of growth in the first 3 years -- the fastest rate of brain development in the entire human lifespan.

Brain Weight

The brain grows at a staggering rate in the first five years.

· By six months, your baby’s brain weighs about half of what it will weigh when he becomes an adult.

· By two years, it weighs three-quarters of what it will weigh in adulthood.

· And by five years, it achieves ninety percent of its adult weight.

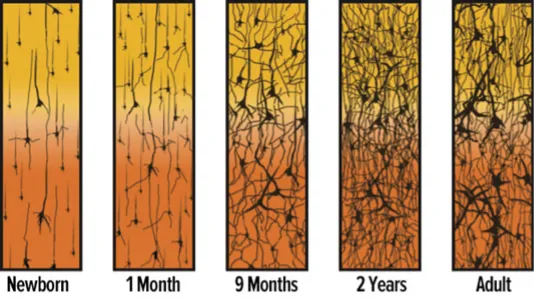

Neuronal Complexity

By the end of the third year, the number of synaptic connections would have reached about 1000 trillion.

2

Activity is the building block of intelligence and knowing.

We have evidence that early experiences impact later cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral functioning.

One type of experience that incorporates all of these domains into one activity is stage-appropriate play. It is the key to cognitive growth.

3

Parents can make a huge difference in their child’s development.

Parent-child interactions are key to a child’s overall development.

The enrichment that parents can provide as a parent cannot be overstated.

Your baby is born ready to learn, discover, and invent. The best time to start is right away!

Book Pricing:

Ebook: $2.99

Softcover $12.99

Hardcover $24.99

Distributers:

Please click of a link below to purchase the book.

Amazon (Paperback only):

https://www.amazon.com/Your-Babys-Brain-Intellect-You/

Barnes & Noble (All formats – eBook, Paperback, Hardcover):

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/your-babys-brain-intellect-and-you-s-h-jacob-ph-d/1147499082?ean=9781967279272

Everand:

https://www.everand.com/book/868152261/Your-Baby-s-Brain-Intellect-and-You-Raising-a-Brilliant-Mind

Empowering parents worldwide with accessible, quality cognitive development for their babies.